Do Most Animal-like Protists Have A Cell Wall

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously depict the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, depict something in its standard anatomical position. This position provides a definition of what is at the front ("anterior"), behind ("posterior") and so on. Every bit part of defining and describing terms, the body is described through the apply of anatomical planes and anatomical axes.

The pregnant of terms that are used can change depending on whether an organism is bipedal or quadrupedal. Additionally, for some animals such as invertebrates, some terms may non have whatsoever meaning at all; for case, an animate being that is radially symmetrical will take no anterior surface, but tin can even so have a description that a part is close to the center ("proximal") or further from the heart ("distal").

International organisations have determined vocabularies that are often used equally standard vocabularies for subdisciplines of anatomy, for example, Terminologia Anatomica for humans, and Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria for animals. These permit parties that apply anatomical terms, such every bit anatomists, veterinarians, and medical doctors to have a standard prepare of terms to communicate clearly the position of a structure.

Introduction [edit]

Because of differences in the fashion humans and other animals are structured, dissimilar terms are used according to the neuraxis and whether an beast is a vertebrate or invertebrate.

Standard anatomical and zoological terms of location accept been adult, usually based on Latin and Greek words, to enable all biological and medical scientists, veterinarians, doctors and anatomists to precisely delineate and communicate data about animal bodies and their organs, even though the pregnant of some of the terms often is context-sensitive.[1] [2] Much of this information has been standardised in internationally agreed vocabularies for humans (Terminologia Anatomica)[2] and animals (Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria).[1]

For humans, one type of vertebrate, and other animals that stand on two feet (bipeds), terms that are used are dissimilar from those that stand on iv (quadrupeds).[ane] One reason is that humans have a unlike neuraxis and another is that unlike animals that balance on four limbs, humans are considered when describing anatomy as being in the standard anatomical position, which is standing upward with artillery outstretched.[2] Thus, what is on "top" of a man is the head, whereas the "top" of a dog may be its dorsum, and the "top" of a flounder could refer to either its left or its correct side. Unique terms are used to draw animals without a backbone (invertebrates), because of their wide variety of shapes and symmetry.[3]

Standard anatomical position [edit]

Because animals can change orientation with respect to their environment, and because appendages like limbs and tentacles can change position with respect to the main body, terms to describe position need to refer to an animal when information technology is in its standard anatomical position.[1] This ways descriptions equally if the organism is in its standard anatomical position, even when the organism in question has appendages in another position. This helps avoid defoliation in terminology when referring to the same organism in unlike postures.[i] In humans, this refers to the torso in a standing position with arms at the side and palms facing frontward, with thumbs out and to the sides.[ii] [1]

Combined terms [edit]

Many anatomical terms can be combined, either to indicate a position in ii axes simultaneously or to indicate the direction of a motion relative to the body. For example, "anterolateral" indicates a position that is both anterior and lateral to the body axis (such as the majority of the pectoralis major muscle).

In radiology, an X-ray image may exist said to exist "anteroposterior", indicating that the axle of Ten-rays passes from their source to patient'southward anterior torso wall through the body to exit through posterior torso wall.[four] Combined terms were in one case generally, hyphenated, merely the modernistic trend is to omit the hyphen.[v]

Planes [edit]

Anatomical planes in a human

Anatomical terms describe structures with relation to four chief anatomical planes:[2]

- The median airplane, which divides the trunk into left and right.[2] [6] This passes through the caput, spinal string, navel, and, in many animals, the tail.[vi]

- The sagittal planes, which are parallel to the median plane.[ane]

- The frontal aeroplane, also chosen the coronal aeroplane, which divides the trunk into front end and dorsum.[2]

- The horizontal plane, also known equally the transverse airplane, which is perpendicular to the other two planes.[2] In a human, this plane is parallel to the ground; in a quadruped, this divides the animal into anterior and posterior sections.[3]

Axes [edit]

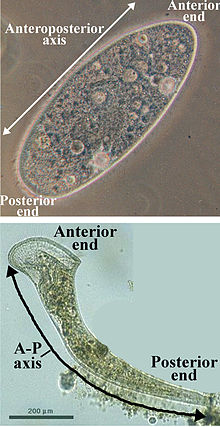

Organisms where the ends of the long axis are singled-out. (Paramecium caudatum, above, and Stentor roeselii, beneath.)

The axes of the body are lines drawn about which an organism is roughly symmetrical.[seven] To do this, distinct ends of an organism are called, and the axis is named co-ordinate to those directions. An organism that is symmetrical on both sides has three main axes that intersect at right angles.[3] An organism that is round or not symmetrical may accept dissimilar axes.[three] Example axes are:

- The anteroposterior axis[8]

- The cephalocaudal axis[9]

- The dorsoventral axis[x]

Examples of axes in specific animals are shown below.

-

Anatomical axes and directions in a fish

-

![Spheroid or near-spheroid organs such as testes may be measured by "long" and "short" axis.[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Long_and_short_axis.png/100px-Long_and_short_axis.png)

Spheroid or nearly-spheroid organs such as testes may exist measured past "long" and "short" axis.[eleven]

Modifiers [edit]

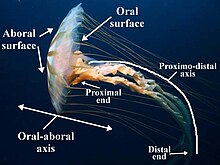

Terms can exist modified with prefixes and suffixes. In this image showing the jellyfish species Chrysaora, the prefix 'ab-', is used to indicate something that is 'abroad from' the rima oris, for example the aboral. Other terms are combined to point axes, such as proximodistal axis.

Several terms are commonly seen and used every bit prefixes:

- Sub- (from Latin sub 'preposition beneath, close to, nigh etc') is used to indicate something that is beneath, or something that is subordinate to or lesser than.[12] For example, subcutaneous ways below the skin, and "subglobular" may mean smaller than a globule

- Hypo- (from Ancient Greek ὑπό 'under') is used to point something that is beneath.[13] For case, the hypoglossal nerve supplies the muscles beneath the natural language.

- Infra- (from Latin infra 'nether') is used to indicate something that is within or below.[xiv] For example, the infraorbital nerve runs within the orbit.

- Inter- (from Latin inter 'betwixt') is used to indicate something that is between.[15] For case, the intercostal muscles run between the ribs.

- Super- or Supra- (from Latin super, supra 'above, on top of') is used to betoken something that is above something else.[16] For example, the supraorbital ridges are in a higher place the eyes.

Other terms are used as suffixes, added to the end of words:

- -advertizing (from Latin ad 'towards') and ab- (from Latin ab) are used to signal that something is towards (-advertizing) or abroad from (-ab) something else.[17] [18] For example, "distad" means "in the distal direction", and "distad of the femur" ways "beyond the femur in the distal direction". Further examples may include cephalad (towards the cephalic cease), craniad, and proximad.[19]

Main terms [edit]

Superior and junior [edit]

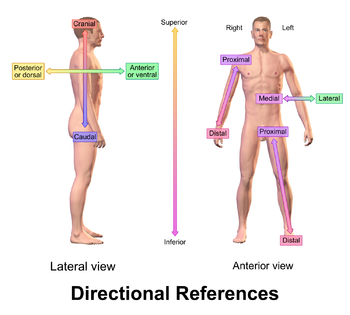

Superior (from Latin super 'above') describes what is above something[xx] and junior (from Latin inferus 'below') describes what is beneath it.[21] For example, in the anatomical position, the most superior function of the human body is the caput and the most junior is the anxiety. As a second example, in humans, the neck is superior to the chest merely inferior to the head.

Anterior and posterior [edit]

Inductive (from Latin ante 'before') describes what is in front,[22] and posterior (from Latin post 'after') describes what is to the back of something.[23] For example, for a dog the nose is inductive to the eyes and the tail is considered the well-nigh posterior part; for many fish the gill openings are posterior to the eyes merely anterior to the tail.

Medial and lateral [edit]

These terms describe how close something is to the midline, or the medial plane.[2] Lateral (from Latin lateralis 'to the side') describes something to the sides of an creature, as in "left lateral" and "right lateral". Medial (from Latin medius 'heart') describes structures close to the midline,[2] or closer to the midline than another structure. For example, in a human being, the arms are lateral to the torso. The genitals are medial to the legs.

The terms "left" and "right" are sometimes used, or their Latin alternatives (Latin: dexter, lit.'right'; Latin: sinister, lit.'left'). Nonetheless, every bit left and correct sides are mirror images, using these words is somewhat disruptive, every bit structures are duplicated on both sides. For example, information technology is very confusing to say the dorsal fin of a fish is "right of" the left pectoral fin, but is "left of" the right eye,[ dubious ] merely much easier and clearer to say "the dorsal fin is medial to the pectoral fins".

Terms derived from lateral include:

- Contralateral (from Latin contra 'against'): on the side opposite to another structure.[24] For example, the right arm and leg are controlled by the left, contralateral, side of the brain.

- Ipsilateral (from Latin ipse 'same'): on the same side equally some other structure.[25] For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg.

- Bilateral (from Latin bis 'twice'): on both sides of the body.[26] For example, bilateral orchiectomy means removal of testes on both sides of the trunk.

- Unilateral (from Latin unus 'ane'): on one side of the body.[27] For example, a stroke can result in unilateral weakness, meaning weakness on one side of the body.

Varus (from Latin 'bow-legged') and valgus (from Latin 'knock-kneed' ) are terms used to describe a state in which a part further away is abnormally placed towards (varus) or abroad from (valgus) the midline.[28]

Proximal and distal [edit]

Anatomical directional reference

The terms proximal (from Latin proximus 'nearest') and distal (from Latin distare 'to stand away from') are used to describe parts of a feature that are close to or afar from the main mass of the body, respectively.[29] Thus the upper arm in humans is proximal and the manus is distal.

"Proximal and distal" are frequently used when describing appendages, such as fins, tentacles, and limbs. Although the direction indicated past "proximal" and "distal" is e'er respectively towards or away from the indicate of attachment, a given construction tin be either proximal or distal in relation to another betoken of reference. Thus the elbow is distal to a wound on the upper arm, simply proximal to a wound on the lower arm.[thirty]

This terminology is also employed in molecular biological science and therefore by extension is besides used in chemical science, specifically referring to the atomic loci of molecules from the overall moiety of a given compound.[31]

Primal and peripheral [edit]

Fundamental and peripheral refer to the distance towards and away from the centre of something.[32] That might be an organ, a region in the trunk, or an anatomical construction. For example, the Fundamental nervous system and the peripheral nervous systems.

Fundamental (from Latin centralis) describes something close to the centre.[32] For example, the great vessels run centrally through the trunk; many smaller vessels branch from these.

Peripheral (from Latin peripheria, originally from Ancient Greek) describes something farther away from the heart of something.[33] For example, the arm is peripheral to the body.

Superficial and deep [edit]

These terms refer to the distance of a construction from the surface.[2]

Deep (from Old English) describes something further away from the surface of the organism.[34] For instance, the external oblique muscle of the abdomen is deep to the skin. "Deep" is one of the few anatomical terms of location derived from Quondam English rather than Latin – the anglicised Latin term would have been "profound" (from Latin profundus 'due to depth').[1] [35]

Superficial (from Latin superficies 'surface') describes something near the outer surface of the organism.[1] [36] For instance, in pare, the epidermis is superficial to the subcutis.

Dorsal and ventral [edit]

These two terms, used in anatomy and embryology, depict something at the back (dorsal) or front end/belly (ventral) of an organism.[2]

The dorsal (from Latin dorsum 'back') surface of an organism refers to the dorsum, or upper side, of an organism. If talking about the skull, the dorsal side is the top.[37]

The ventral (from Latin venter 'belly') surface refers to the front, or lower side, of an organism.[37]

For example, in a fish, the pectoral fins are dorsal to the anal fin, but ventral to the dorsal fin.

Cranial and caudal [edit]

In the homo skull, the terms rostral and caudal are adjusted to the curved neuraxis of Hominidae, rostrocaudal meaning the region on C shape connecting rostral and caudal regions.

Specific terms exist to describe how close or far something is to the caput or tail of an animal. To describe how close to the head of an animal something is, three singled-out terms are used:

- Rostral (from Latin rostrum 'beak, nose') describes something situated toward the oral or nasal region, or in the case of the brain, toward the tip of the frontal lobe.[38]

- Cranial (from Greek κρανίον 'skull') or cephalic (from Greek κεφαλή 'caput') describes how shut something is to the head of an organism.[39]

- Caudal (from Latin cauda 'tail') describes how close something is to the trailing finish of an organism.[40]

For example, in horses, the eyes are caudal to the nose and rostral to the back of the caput.

These terms are generally preferred in veterinary medicine and not used every bit often in human medicine.[41] [42] [43] In humans, "cranial" and "cephalic" are used to refer to the skull, with "cranial" being used more than ordinarily. The term "rostral" is rarely used in man anatomy, apart from embryology, and refers more to the front end of the face than the superior aspect of the organism. Similarly, the term "caudal" is used more than in embryology and only occasionally used in human being anatomy.[ii] This is because the encephalon is situated at the superior role of the caput whereas the nose is situated in the anterior role. Thus, the "rostrocaudal axis" refers to a C shape (see image).

Other terms and special cases [edit]

Anatomical landmarks [edit]

The location of anatomical structures tin can also exist described in relation to different anatomical landmarks. They are used in anatomy, surface anatomy, surgery, and radiology.[44]

Structures may be described every bit being at the level of a specific spinal vertebra, depending on the section of the vertebral column the construction is at.[44] The position is often abbreviated. For instance, structures at the level of the 4th cervical vertebra may exist abbreviated as "C4", at the level of the quaternary thoracic vertebra "T4", and at the level of the 3rd lumbar vertebra "L3". Considering the sacrum and coccyx are fused, they are non oftentimes used to provide the location.

References may also take origin from superficial beefcake, made to landmarks that are on the peel or visible underneath.[44] For example, structures may be described relative to the anterior superior iliac spine, the medial malleolus or the medial epicondyle.

Anatomical lines are used to describe anatomical location. For example, the mid-clavicular line is used as part of the cardiac exam in medicine to feel the apex beat of the heart.

Oral fissure and teeth [edit]

Special terms are used to describe the mouth and teeth.[2] Fields such every bit osteology, palaeontology and dentistry utilize special terms of location to describe the rima oris and teeth. This is because although teeth may be aligned with their primary axes inside the jaw, some different relationships require special terminology equally well; for example, teeth too can be rotated, and in such contexts terms similar "anterior" or "lateral" become ambiguous.[45] [46] For case, the terms "distal" and "proximal" are also redefined to hateful the altitude abroad or close to the dental curvation, and "medial" and "lateral" are used to refer to the closeness to the midline of the dental arch.[47] Terms used to describe structures include "buccal" (from Latin bucca 'cheek') and "palatal" (from Latin) referring to structures close to the cheek and hard palate respectively.[47]

Hands and feet [edit]

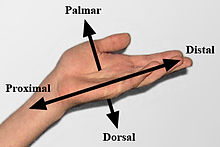

Anatomical terms used to describe a homo paw

Several anatomical terms are item to the easily and feet.[ii]

Additional terms may exist used to avoid confusion when describing the surfaces of the hand and what is the "anterior" or "posterior" surface – . The term "anterior", while anatomically correct, can be confusing when describing the palm of the hand; Similarly is "posterior", used to describe the back of the paw and arm. This confusion can arise considering the forearm tin can pronate and supinate and flip the location of the hand. For improved clarity, the directional term palmar (from Latin palma 'palm of the hand') is commonly used to describe the front of the manus, and dorsal is the back of the paw. For example, the top of a dog's mitt is its dorsal surface; the underside, either the palmar (on the forelimb) or the plantar (on the hindlimb) surface. The palmar fascia is palmar to the tendons of muscles which flex the fingers, and the dorsal venous arch is and so named because it is on the dorsal side of the pes.

In humans, volar can too exist used synonymously with palmar to refer to the underside of the palm, but plantar is used exclusively to draw the sole. These terms draw location as palmar and plantar; For case, volar pads are those on the underside of hands or fingers; the plantar surface describes the sole of the heel, foot or toes.

Similarly, in the forearm, for clarity, the sides are named after the bones. Structures closer to the radius are radial, structures closer to the ulna are ulnar, and structures relating to both bones are referred to as radioulnar. Similarly, in the lower leg, structures well-nigh the tibia (shinbone) are tibial and structures near the fibula are fibular (or peroneal).

Rotational management [edit]

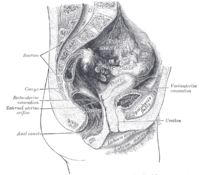

Anteversion and retroversion are complementary terms describing an anatomical structure that is rotated frontwards (towards the front end of the body) or backwards (towards the dorsum of the torso), relative to some other position. They are particularly used to describe the curvature of the uterus.[48] [49]

- Anteversion (from Latin anteversus) describes an anatomical structure beingness tilted further forward than normal, whether pathologically or incidentally.[48] For case, a woman'southward uterus typically is anteverted, tilted slightly forrad. A misaligned pelvis may exist anteverted, that is to say tilted frontward to some relevant degree.

- Retroversion (from Latin retroversus) describes an anatomical structure tilted back away from something.[49] An example is a retroverted uterus.[49]

Other directional terms [edit]

Several other terms are also used to describe location. These terms are not used to form the fixed axes. Terms include:

- Centric (from Latin axis 'beam'): around the central centrality of the organism or the extremity. Two related terms, "abaxial" and "adaxial", refer to locations away from and toward the central axis of an organism, respectively

- Luminal (from Latin lumen 'lite, opening'): on the—hollow—within of an organ's lumen (trunk crenel or tubular structure);[50] [51] adluminal is towards, abluminal is abroad from the lumen.[52] Opposite to outermost (the adventitia, serosa, or the cavity's wall).[53]

- Parietal (from Latin paries 'wall'): pertaining to the wall of a torso crenel.[54] For instance, the parietal peritoneum is the lining on the inside of the abdominal cavity. Parietal tin can also refer specifically to the parietal os of the skull or associated structures.

- Final (from Latin terminus 'boundary or finish') at the extremity of a usually projecting structure.[55] For example, "...an antenna with a terminal sensory pilus".

- Visceral and viscus (from Latin viscera 'internal organs'): associated with organs within the body's cavities.[56] For example, the tum is covered with a lining chosen the visceral peritoneum as opposed to the parietal peritoneum. Viscus can also be used to hateful "organ".[56] For example, the breadbasket is a viscus within the intestinal cavity, and visceral pain refers to pain originating from internal organs.

- Aboral (contrary to oral) is used to announce a location along the gastrointestinal canal that is relatively closer to the anus.[57]

Specific animals and other organisms [edit]

Unlike terms are used considering of different body plans in animals, whether animals stand up on one or two legs, and whether an animal is symmetrical or not, as discussed higher up. For case, every bit humans are approximately bilaterally symmetrical organisms, anatomical descriptions normally utilise the same terms as those for other vertebrates.[58] All the same, humans stand up upright on two legs, meaning their anterior/posterior and ventral/dorsal directions are the aforementioned, and the junior/superior directions are necessary.[59] Humans practise not have a nib, so a term such as "rostral" used to refer to the bill in some animals is instead used to refer to part of the brain;[60] humans do as well non have a tail so a term such as "caudal" that refers to the tail end may also be used in humans and animals without tails to refer to the hind part of the torso.[61]

In invertebrates, the large variety of torso shapes presents a difficult problem when attempting to apply standard directional terms. Depending on the organism, some terms are taken by analogy from vertebrate anatomy, and appropriate novel terms are applied as needed. Some such borrowed terms are widely applicable in about invertebrates; for example proximal, meaning "about" refers to the part of an appendage nearest to where it joins the body, and distal, meaning "standing away from" is used for the part furthest from the signal of zipper. In all cases, the usage of terms is dependent on the body plan of the organism.

-

Anatomical terms of location in a dog

-

Anatomical terms of location in a kangaroo

-

Anatomical terms of location in a fish.

-

Anatomical terms of location in a horse.

Asymmetrical and spherical organisms [edit]

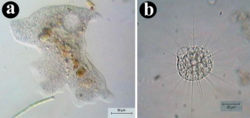

Asymmetrical and spherical trunk shapes. (a) An organism with an asymmetrical, amoeboid, body programme (Amoeba proteus – an amoeba). (b) An organism with a spherical trunk programme (Actinophrys sol – a heliozoan).

In organisms with a changeable shape, such as amoeboid organisms, most directional terms are meaningless, since the shape of the organism is not abiding and no distinct axes are fixed. Similarly, in spherically symmetrical organisms, at that place is cipher to distinguish one line through the centre of the organism from any other. An indefinite number of triads of mutually perpendicular axes could be defined, just any such choice of axes would be useless, as cipher would distinguish a chosen triad from whatever others. In such organisms, merely terms such as superficial and deep, or sometimes proximal and distal, are usefully descriptive.

4 individuals of Phaeodactylum tricornutum, a diatom with a fixed elongated shape.

Elongated organisms [edit]

In organisms that maintain a constant shape and have i dimension longer than the other, at least two directional terms tin be used. The long or longitudinal axis is divers by points at the contrary ends of the organism. Similarly, a perpendicular transverse axis can be defined past points on opposite sides of the organism. There is typically no footing for the definition of a third axis. Usually such organisms are planktonic (free-swimming) protists, and are nearly ever viewed on microscope slides, where they appear essentially two-dimensional. In some cases a tertiary axis can exist defined, particularly where a non-terminal cytostome or other unique structure is nowadays.[43]

Some elongated protists have distinctive ends of the trunk. In such organisms, the end with a rima oris (or equivalent structure, such as the cytostome in Paramecium or Stentor), or the end that usually points in the direction of the organism's locomotion (such as the stop with the flagellum in Euglena), is ordinarily designated as the anterior end. The opposite end then becomes the posterior end.[43] Properly, this terminology would employ but to an organism that is e'er planktonic (non unremarkably attached to a surface), although the term can also exist applied to one that is sessile (commonly attached to a surface).[62]

Organisms that are fastened to a substrate, such as sponges, creature-like protists besides have distinctive ends. The part of the organism attached to the substrate is usually referred to every bit the basal stop (from Latin basis 'back up/foundation'), whereas the finish furthest from the attachment is referred to as the upmost end (from Latin apex 'acme/tip').

Radially symmetrical organisms [edit]

Radially symmetrical organisms include those in the group Radiata – primarily jellyfish, sea anemones and corals and the rummage jellies.[41] [43] Adult echinoderms, such equally starfish, body of water urchins, sea cucumbers and others are also included, since they are pentaradial, pregnant they have five detached rotational symmetry. Echinoderm larvae are not included, since they are bilaterally symmetrical.[41] [43] Radially symmetrical organisms e'er have one distinctive axis.

Cnidarians (jellyfish, bounding main anemones and corals) accept an incomplete digestive organization, meaning that one end of the organism has a mouth, and the opposite end has no opening from the gut (coelenteron).[43] For this reason, the finish of the organism with the rima oris is referred to as the oral end (from Latin ōrālis 'of the mouth'),[63] and the opposite surface is the aboral end (from Latin ab- 'away from').[64]

Different vertebrates, cnidarians accept no other distinctive axes. "Lateral", "dorsal", and "ventral" take no significant in such organisms, and all tin be replaced by the generic term peripheral (from Ancient Greek περιφέρεια 'circumference'). Medial can be used, but in the example of radiates indicates the key point, rather than a central centrality as in vertebrates. Thus, there are multiple possible radial axes and medio-peripheral (half-) axes. However, some biradially symmetrical comb jellies practise accept distinct "tentacular" and "pharyngeal" axes[65] and are thus anatomically equivalent to bilaterally symmetrical animals.

-

Aurelia aurita, some other species of jellyfish, showing multiple radial and medio-peripheral axes

-

The sea star Porania pulvillus, aboral and oral surfaces

Spiders [edit]

Special terms are used for spiders. 2 specialized terms are useful in describing views of arachnid legs and pedipalps. Prolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the anterior terminate of an arachnid's body. Retrolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the posterior cease of an arachnid'due south body.[66] Nearly spiders have eight eyes in four pairs. All the eyes are on the carapace of the prosoma, and their sizes, shapes and locations are feature of various spider families and other taxa.[67] Usually, the optics are arranged in 2 roughly parallel, horizontal and symmetrical rows of eyes.[67] Eyes are labelled according to their position every bit anterior and posterior lateral eyes (ALE) and (PLE); and anterior and posterior median eyes (AME) and (PME).[67]

-

Aspects of spider anatomy; This attribute shows the mainly prolateral surface of the anterior femora, plus the typical horizontal eye pattern of the Sparassidae

-

Typical system of eyes in the Lycosidae, with PME beingness the largest

Run across likewise [edit]

- Chirality

- Geometric terms of location

- Handedness

- Laterality

- Proper right and proper left

- Reflection symmetry

- Sinistral and dextral

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dyce, Sack & Wensing 2010, pp. ii–3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 grand n o Gray'south Anatomy 2016, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^ a b c d Kardong's 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Hofer, Matthias (2006). The Chest X-ray: A Systematic Educational activity Atlas. Thieme. p. 24. ISBN978-3-thirteen-144211-half-dozen.

- ^ "dorsolateral". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Wake 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Collins 2020, "axis", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Anteroposterior", accessed fourteen October 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Cephalocaudal", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Dorsoventral", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^ Pellerito, John; Polak, Joseph F. (2012). Introduction to Vascular Ultrasonography (6th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 559. ISBN978-1-4557-3766-6.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Sub-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Hypo-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Infra-", accessed on three July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Inter-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "Super-" and "Supra-", accessed on three July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "-ad", accessed on three July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "an-", accessed on 17 July 2020.

- ^ Gordh, Gordon; Headrick, David H (2011). A Dictionary of Entomology (2nd ed.). CABI. ISBN978-1845935429.

- ^ Collins 2020, "superior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "junior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "anterior", accessed ii July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "posterior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "contralateral", accessed two July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "ipsilateral", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "bilateral", accessed ii July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "unilateral", accessed ii July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "varus" and "valgus", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ Wake 1992, p. 5.

- ^ "What Do Distal and Proximal Mean?". The Survival Doctor. 2011-ten-05. Retrieved 2016-01-07 .

- ^ Singh, South (8 March 2000). "Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists". Chemical Reviews. 100 (3): 925–1024. doi:10.1021/cr9700538. PMID 11749256.

- ^ a b Collins 2020, "cardinal", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "peripheral", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "deep", accessed ii July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "profound", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ Collins 2020, "superficial", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b Go 2014, "dorsal/ventral centrality specification" (GO:0009950).

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "rostral", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "cranial" and "cephalic", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "caudal", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Hickman, C. P. Jr., Roberts, L. Due south. and Larson, A. Beast Diversity. McGraw-Hill 2003 ISBN 0-07-234903-four

- ^ Miller, South. A. General Zoology Laboratory Manual McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-252837-0 and ISBN 0-07-243559-3

- ^ a b c d eastward f Ruppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004). Invertebrate zoology : a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. ISBN0-03-025982-7.

- ^ a b c Butler, Paul; Mitchell, Adam W. 1000.; Ellis, Harold (1999-10-14). Applied Radiological Beefcake. Cambridge University Printing. p. 1. ISBN978-0-521-48110-half dozen.

- ^ Pieter A. Folkens (2000). Human Osteology. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 558–. ISBN978-0-12-746612-5.

- ^ Smith, J. B.; Dodson, P. (2003). "A proposal for a standard terminology of anatomical annotation and orientation in fossil vertebrate dentitions". Periodical of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (one): one–12. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[one:APFAST]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Rajkumar, K.; Ramya, R. (2017). Textbook of Oral Beefcake, Physiology, Histology and Tooth Morphology. Wolters kluwer india Pvt Ltd. pp. half-dozen–7. ISBN978-93-86691-16-iii.

- ^ a b Collins 2020, "anteversion", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Collins 2020, "retroversion", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^ William C. Shiel. "Medical Definition of Lumen". MedicieNet. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms "lumen"". National Cancer Constitute. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ ""abluminal"". Merriam-Webster.com Medical Dictionary . Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ David Male monarch (2009). "Written report Guide - Histology of the Gastrointestinal System". Southern Illinois University. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "parietal", accessed iii July 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "terminal", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster 2020, "visceral", accessed three July 2020.

- ^ Morrice, Michael; Polton, Gerry; Beck, Sam (2019). "Evaluation of the extent of neoplastic infiltration in small intestinal tumours in dogs". Veterinary Medicine and Science. 5 (two): 189–198. doi:10.1002/vms3.147. ISSN 2053-1095. PMC6498519. PMID 30779310.

- ^ Wake 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Tucker, T. Yard. (1931). A Curtailed Etymological Lexicon of Latin. Halle (Saale): Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "rostral", accessed xiv Oct 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "caudal", accessed 14 Oct 2020.

- ^ Valentine, James Westward. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^ Collins 2020, "oral", accessed thirteen October 2020.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2020, "aboral", accessed xiii October 2020.

- ^ Ruppert et al. (2004), p. 184.

- ^ Kaston, B.J. (1972). How to Know the Spiders (third ed.). Dubuque, IA: West.C. Brown Co. p. xix. ISBN978-0-697-04899-eight. OCLC 668250654.

- ^ a b c Foelix, Rainer (2011). Biology of Spiders. Oxford University Printing, USA. pp. 17–19. ISBN978-0-19-973482-5.

General sources [edit]

- "Collins Online Dictionary | Definitions, Thesaurus and Translations". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- Dyce, KM; Sack, WO; Wensing, CJG (2010). Textbook of veterinary anatomy (4th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN9781416066071.

- "GeneOntology". GeneOntology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Retrieved 26 Oct 2014.

- Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). Grey'southward anatomy: the anatomical footing of clinical exercise (41st ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- Kardong, Kenneth (2019). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution (eighth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN9781260092042.

- "Dictionary past Merriam-Webster: America's almost-trusted online dictionary". world wide web.merriam-webster.com.

- Wake, Marvale H., ed. (1992). Hyman'due south comparative vertebrate beefcake (3rd ed.). Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN9780226870113.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatomical_terms_of_location

Posted by: tedrowagainto.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Do Most Animal-like Protists Have A Cell Wall"

Post a Comment